Norris Dam Visitor Experience

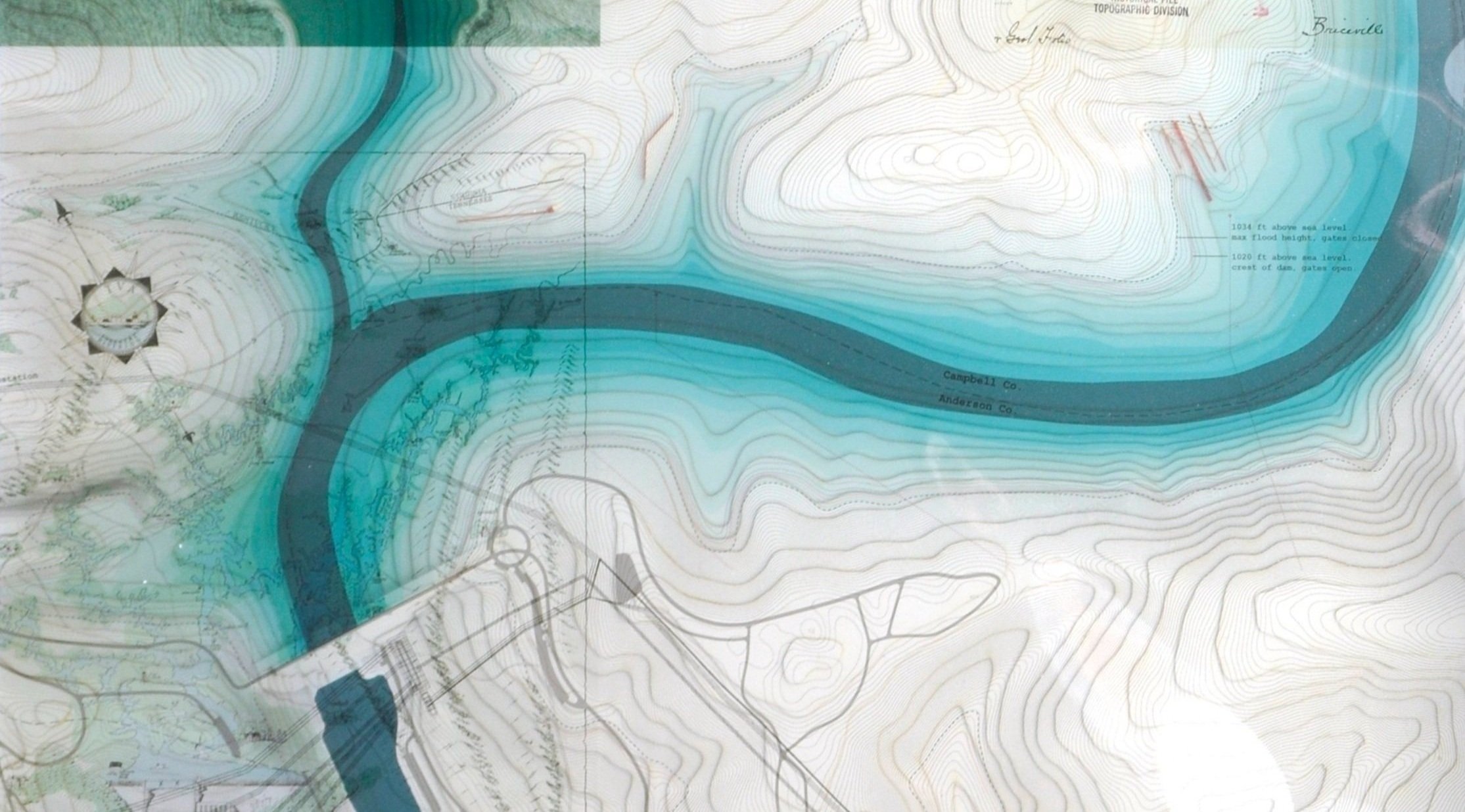

A study on the impact of lines at Norris Dam on the Clinch River in Tennessee through the design of a series of visitor experiences.

BOAT LAUNCH: In plan, the defining water line of the area is no longer the snaking line of the Clinch River, but rather the ever-changing water level. The boat launch was designed as a series of lines jutting into the lake to provide various functions, such as boat launching, docking, pavilions, and water runoff. Various platforms are designed to float and manage the drastically changing water levels, while other moments are meant to remain rigid to call attention to the new defining line.

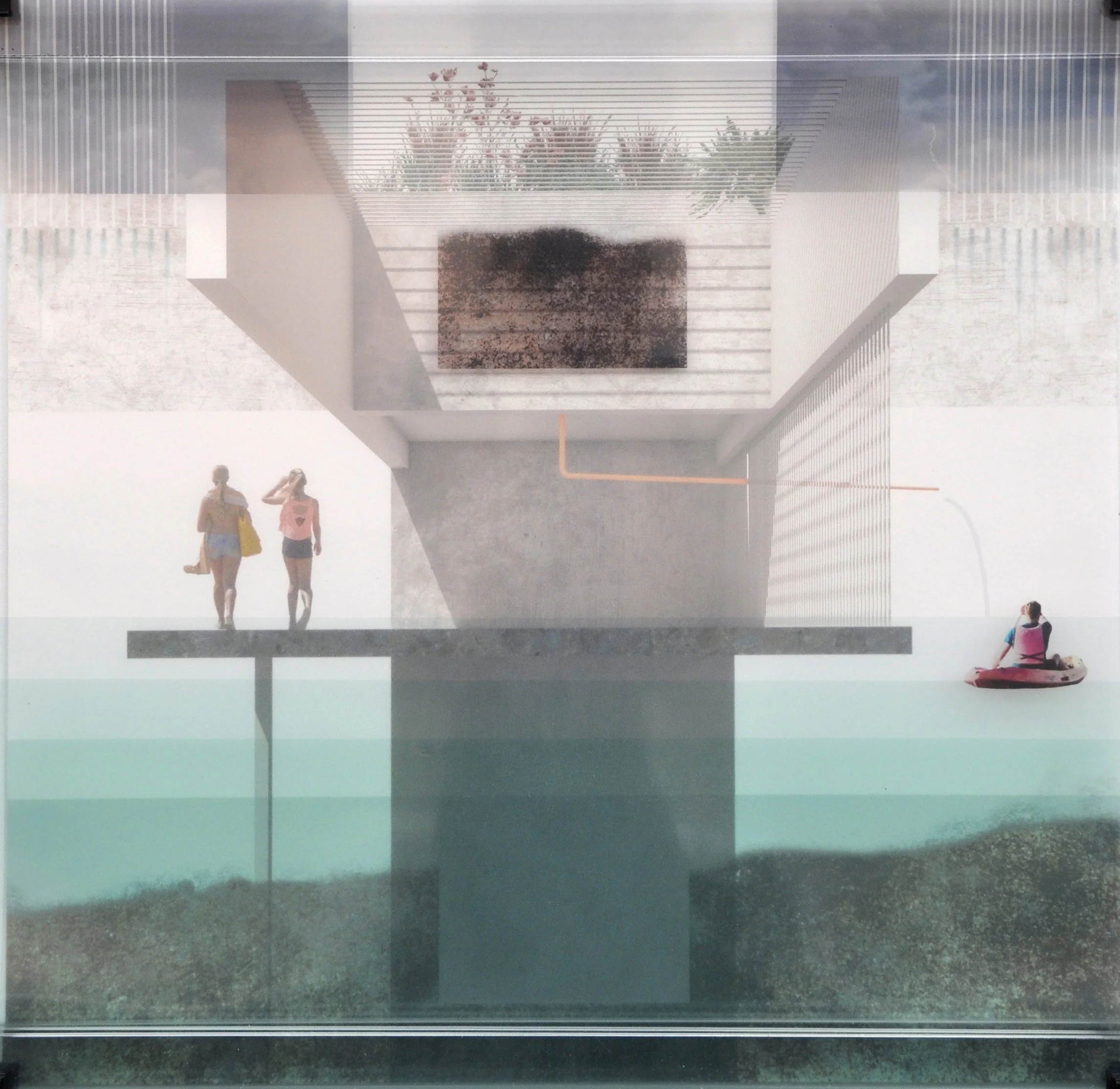

The SWIMMING HOLE is located in an inlet near the dam and consists of a beach area, floating platforms, an elevated dock, and climbing bars extending to the middle of the inlet. The beach is formed by a dramatic cut into the side of the hill which is held back by massive sheet steel piling. The cut is meant to reflect the intensity of certain infrastructures (ie the dam) in contrast to more flexible infrastructures (ie the floating platforms). The platforms are anchored to the lake bottom with varying length of chains so that at certain water levels the platforms are loose, taught, or partially covered. The platforms are arranged as an archipelago that extend from the interior of the inlet out to the original centerline of the Clinch River.

The OBSERVATION TOWER provides a sequence of experiences that relate the visitor to specific elements: the ground, the sky, and the dam. The tower’s plan is carefully designed to pattern the ascent between interior focus and exterior relief. The walls are angled in such a way that as one is climbing the exterior stairs, they cannot see the dam. The interiors are divided vertically into rooms with extreme sectional qualities to focus views on one of the previously mentioned elements, between the themed rooms are rooms for reset that have no view, only diffuse light. The sequence is (from bottom to top): entry, ground, reset, sky, reset, dam, open panorama to the entire landscape. The materiality of the tower is designed to exhibit weathering by lining spouts and gutters with copper so that the oxidation will stain the side of the vertical notch that acts as downspout.

Castle Grange

The tower house—a castle type that dots the landscape of Scotland and Ireland is a singular stone tower surrounded by outer walls within an agrarian landscape. Within the tower, rooms are stacked to culminate with a great hall that commands a view across the countryside.

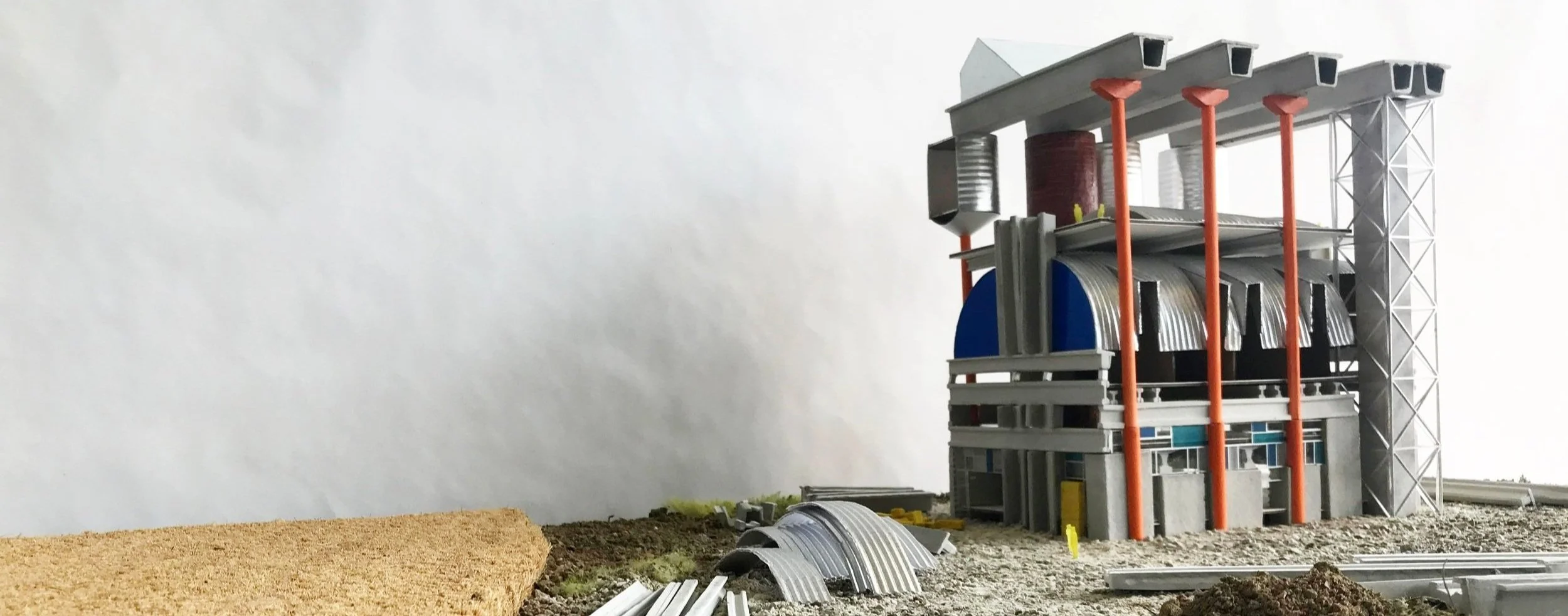

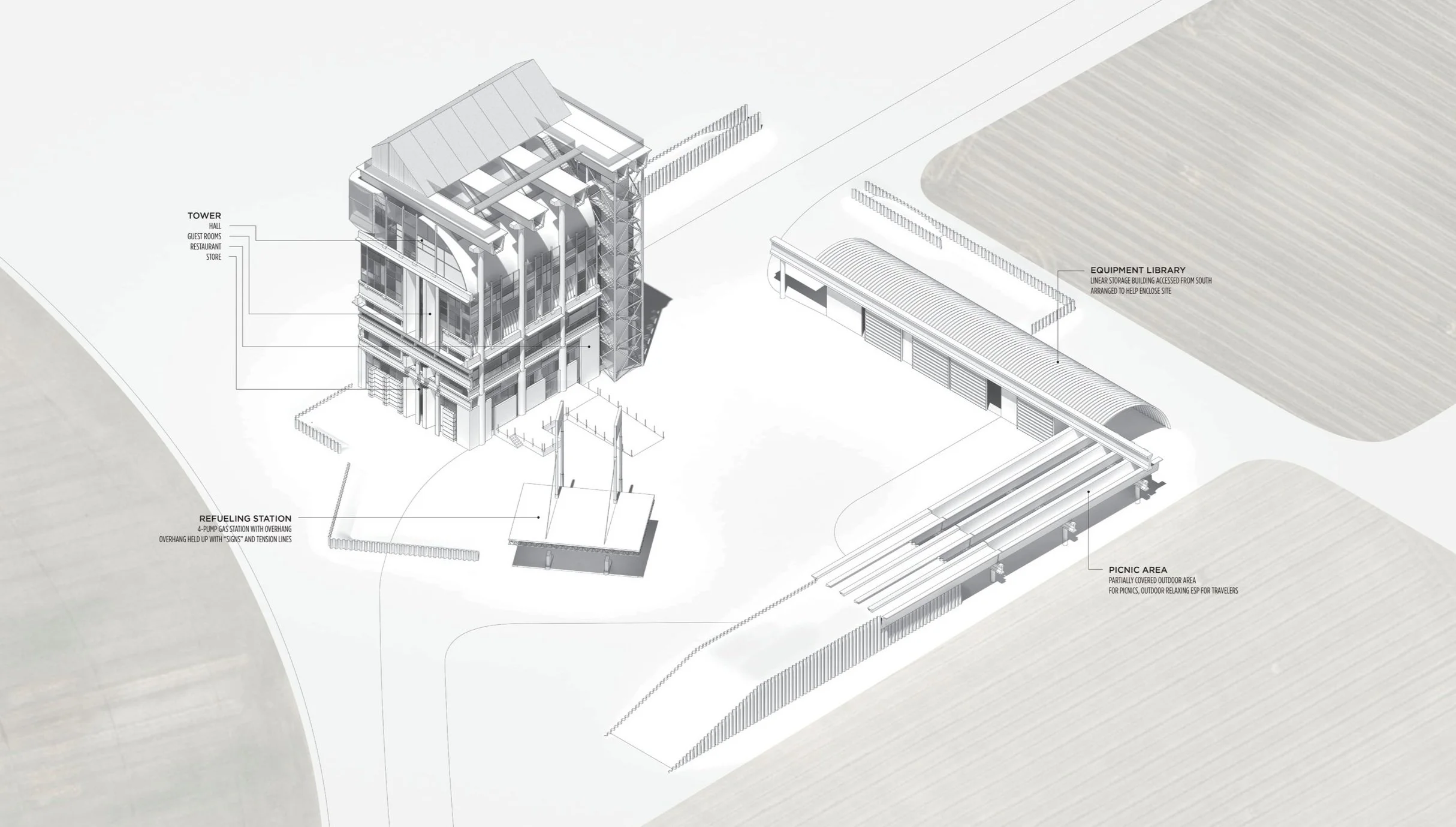

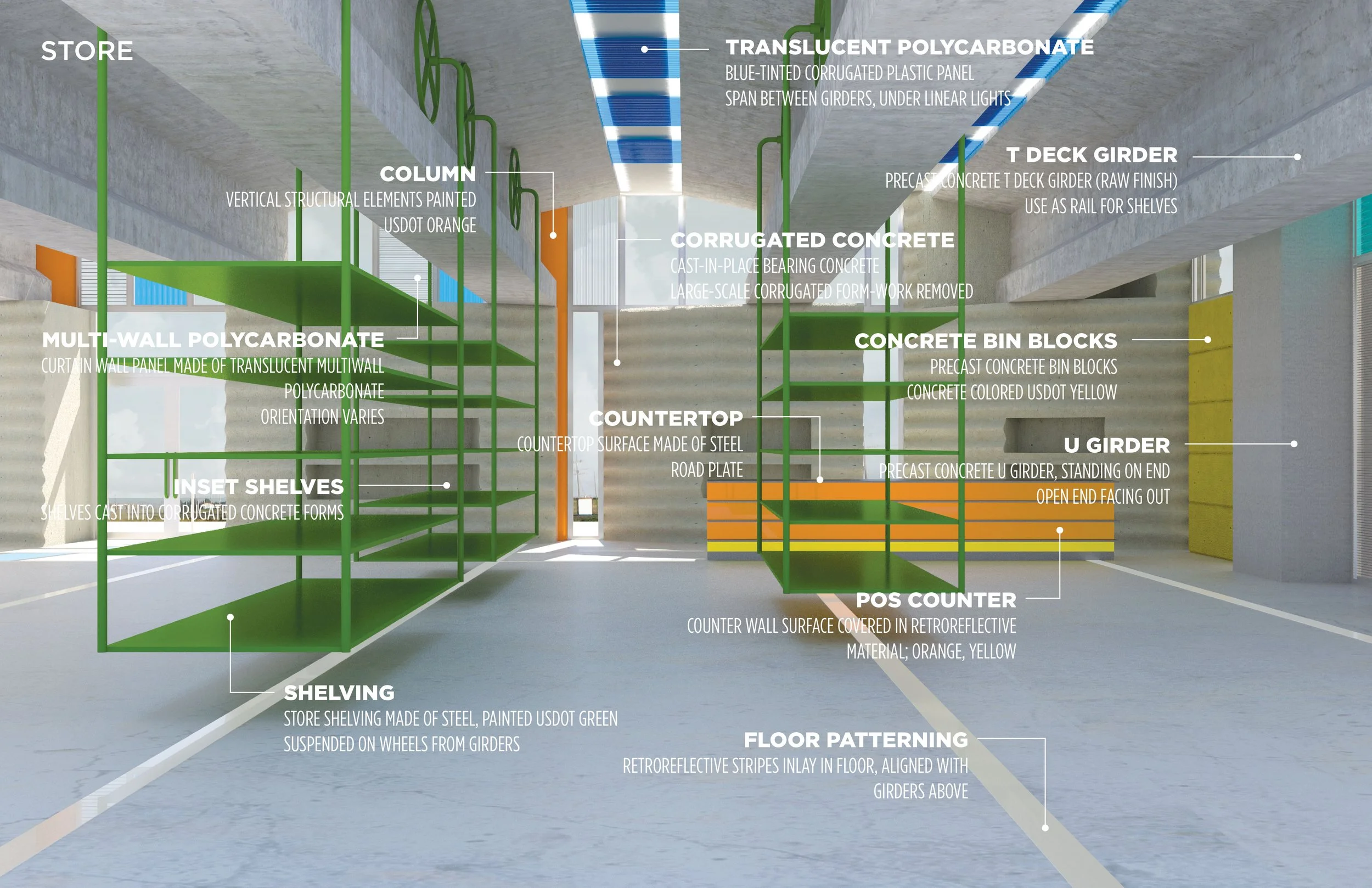

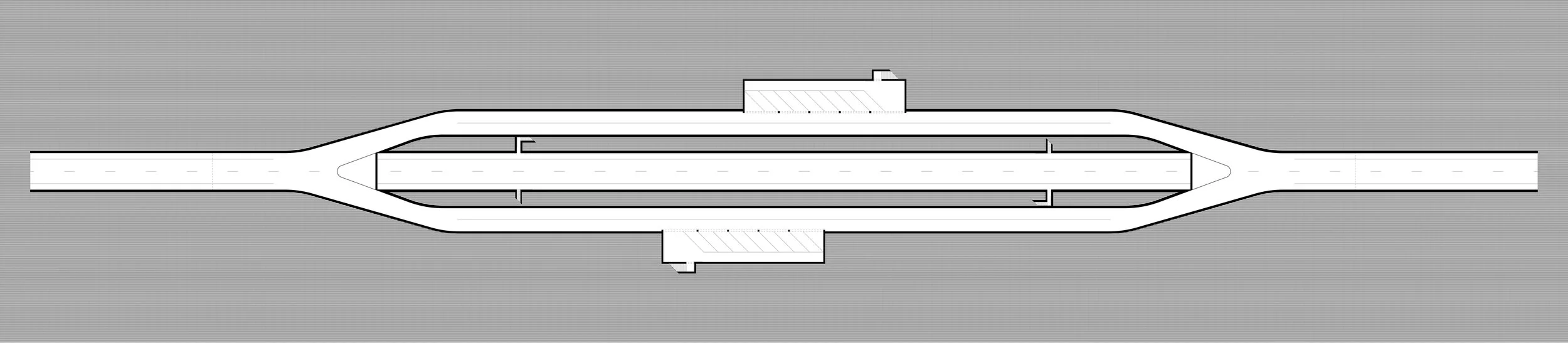

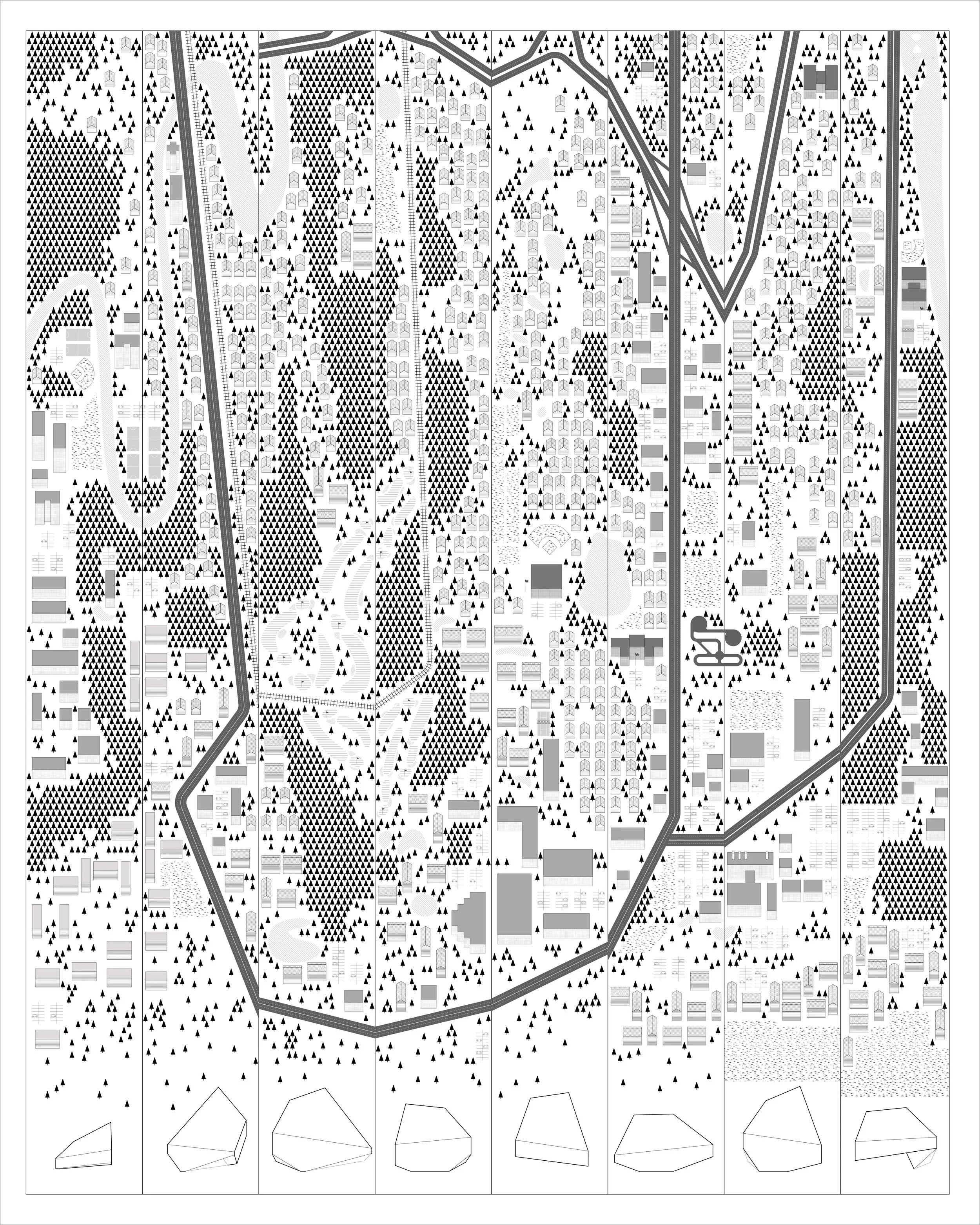

An interstate highway carries 28,000 vehicles a day past exit 373 through the plains of Nebraska. The dispersed landscape is dotted with farms (quaint and factory), towns (small and medium), and service stations (unimpactful and unimpactful)—all divided by yet linked with Interstate 80.

The premise of this project is that these two situations are surprisingly related. The tower house castle was an agrarian bulking-point along trade routes through the medieval countryside similar to the contemporary waystation along America’s highways. As a model for architectural design, the castle injects increased potentials for the waystation typology, especially in the manner in which it is assembled.

Tower house castles were typically assembled through materials found on site, nearby, from quarrying the landscape, and cannibalizing other structures, thereby providing a castle that is born of its site. In the spirit of this technique, Castle Grange establishes the landscape as a catchment area to quarry for materials, colors, and forms. By using the techniques of bricolage, the design concentrates the materiality of the site like a bulking-point for the texture of the Castle Grange.

Highway Land Project

The goal of this design project was to design a walk along or within a “line” (Highway 20 in Iowa) that alters the occupant’s relationship to and perception of ground.

“[T]he very places where the wayfarer pauses for rest are, for the transported passenger, sites of activity. But this activity, confined within a place, is all concentrated on one spot. In between sites he barely skims the surface of the world, if not skipping it entirely, leaving no trace of having passed by or even any recollection of the journey. Indeed the tourist may be advised to expunge from memory the experience of getting there, however arduous or eventful it may have been, lest it should bias or detract from the appreciation of what he as come to see. In effect, the practice of transport converts every trail into the equivalent of a dotted line.”

Tim Ingold, Lines 2016, 81

Fire Station No. 5

An exploration on how the data of a district can impact the design of its fire station.

This fire station is designed from—and as a representation of—the data of its district. Its content is derived from two contrasting distances from the fire station to the buildings in its district: the fictional, direct, “as-the-crow-flies” distances and their corresponding actual, driving distances. These contrasting distances are translated into roofline heights—the former around the courtyard and correspondingly to the latter around the exterior. The building’s surface is mapped with zoned aggregate to represent the densities of the community. The more aggregate, the more firefighters must protect; the more volume, the more difficult it is for them to do that.

Garden for Communities

With help from chance, this project investigates the public garden as a landscape for entertainment and martial arts. Formal garden elements are engaged as the ordering system for play.

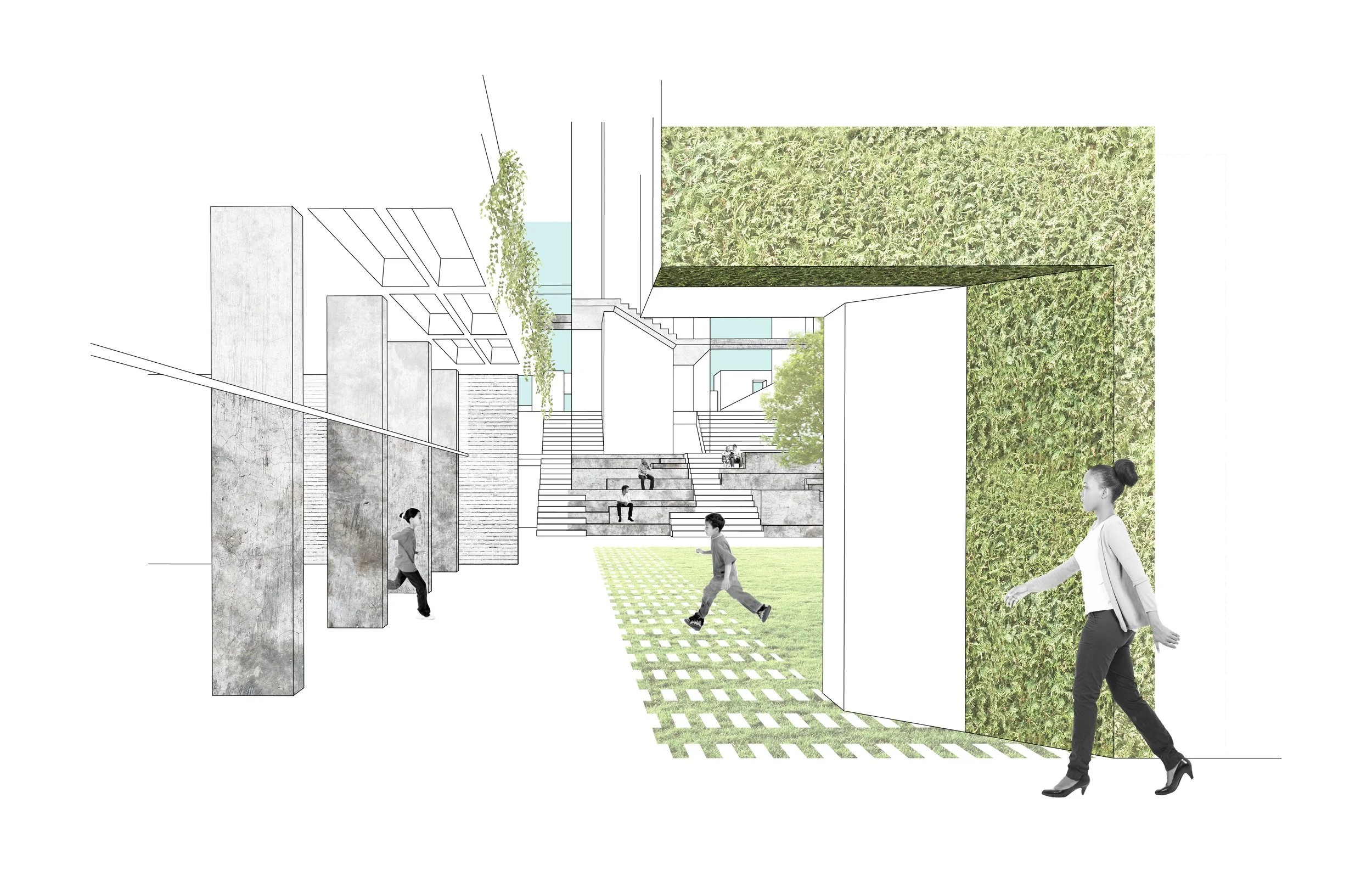

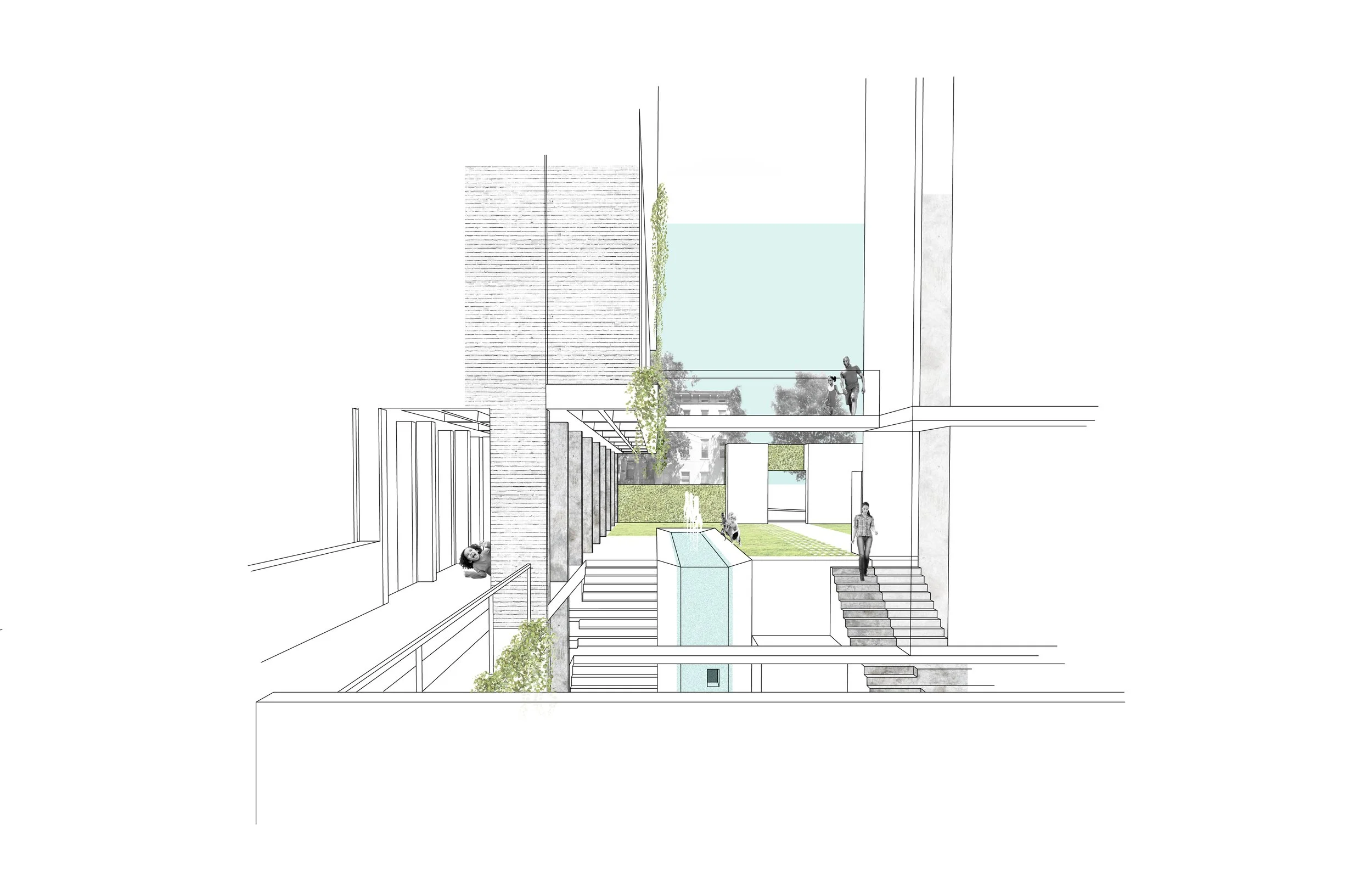

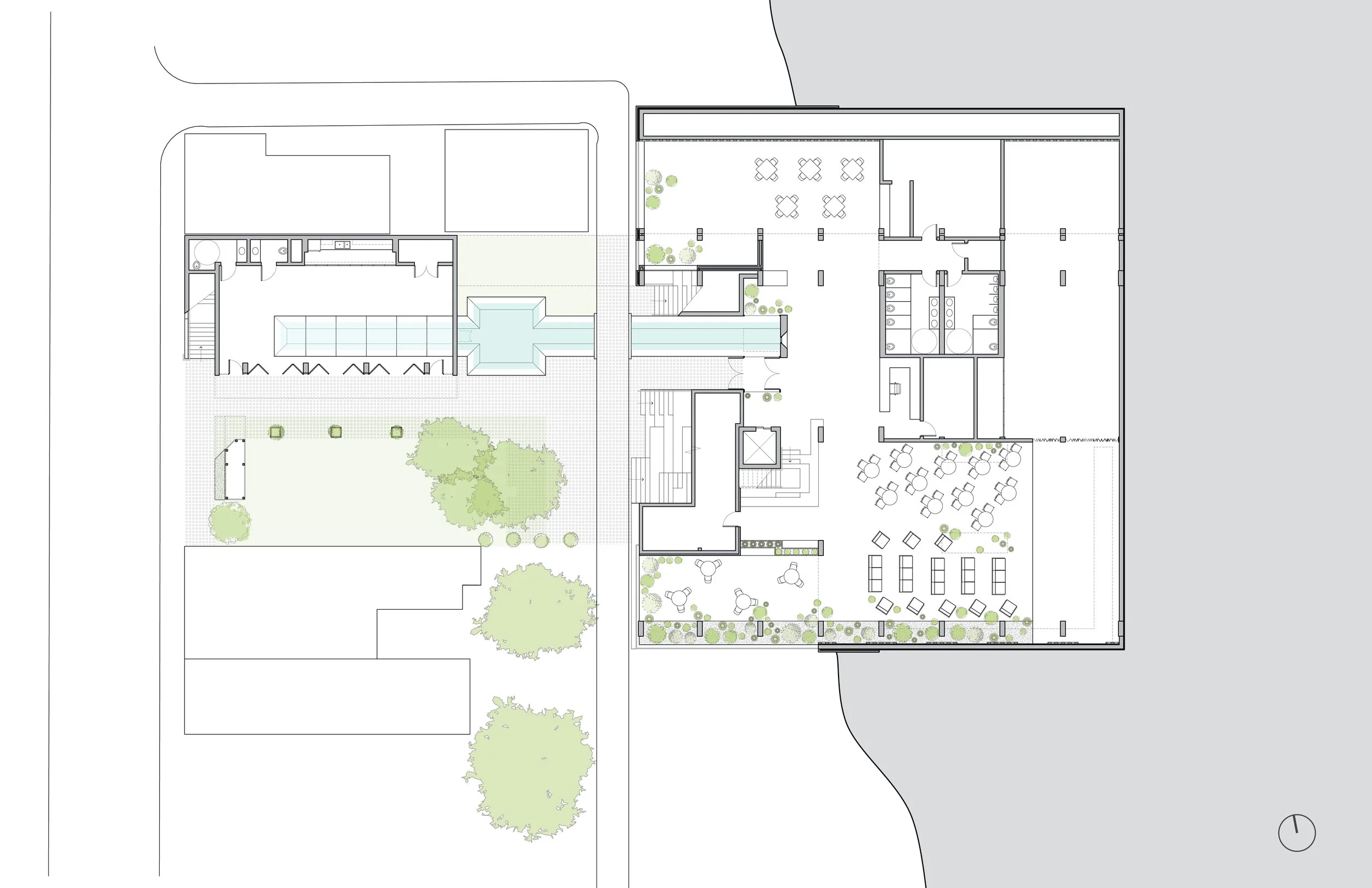

The site for this project is at the junction of several neighborhoods in Cincinnati with varying populations, as well as between Hughes and Sycamore streets with Cogswell Alley running through it. The assigned program was a martial arts and community center which includes two apartments for instructors and a program I chose: performing arts. As a challenge for this studio chance was incorporated into the design process to investigate its effects. Two words were drawn from a hat: “garden(s)” as an architectural operation/ idea and “concrete frame” as the structural system. Formal gardens were researched to identify typologies of gardens and to massage some of the formal elements into communal elements of play.

The strategy of the design was to treat the martial arts as the primary building and raise it on a type of piano nobile and put other major programming under a Sycamore-level garden including a winter garden/performance space; to connect Hughes and Sycamore through the site with a central plaza and performance space; to link it all with multi-level circulation and interactive canal; to incorporate an after-school space on the west side of the site which is conceived of after an orangerie that opens completely to the Hughes level garden.